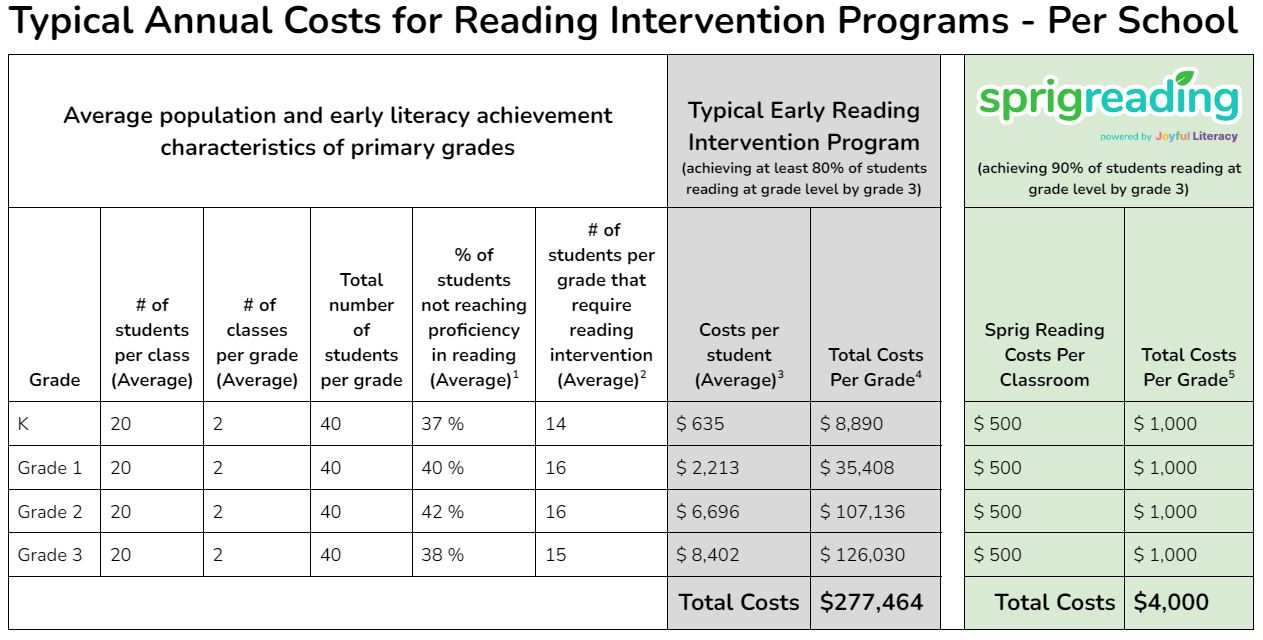

Evidence-Based and Cost-Effective Reading Intervention

When making decisions on education investments, both cost and efficiency must be taken into account. Both factor into the academic ROI, where the idea is to maximize student achievement for a certain sum spent.

There are many studies that explore the impact of educational tools, but the cost-effectiveness of these tools is often overlooked.

Costs include the price tag of such tools, but also the cost of the resources that are required for their successful implementation.

With the launch of Sprig Reading for the upcoming school year, it is a great time to discuss cost-effectiveness in raising reading achievement. Sprig Reading is meant to be an evidence-based, affordable solution for educators to improve the literacy scores of their students.

Reading Intervention Can be Very Expensive

In a cost-effectiveness analysis of 7 early literacy programs that have been effective at improving reading outcomes for K-3 students, the cost per student was associated with the grade level and students’ reading struggles.

For students at higher grade levels (e.g., Grade 3) and those that are really struggling (e.g., bottom 25th percentile), program costs were as much as $10,108 per student (or over $200,000 for a typical classroom of 20 students)!

For students in Grade 1 who were scoring in the bottom 20th percentile, the cost per student was $4,144. For kindergarten students, who were scoring well below average in the bottom 20th-30th percentile, the costs were $791 per student.

For students in Grade 1 scoring slightly below average, the cost per student was $282. Despite being at a higher grade than kindergarten, the cost implications were lower because of the focus on students who were struggling, but closer to the 50th percentile.

Besides grade level and reading struggles, program duration also heavily influenced the pricing per student. The shortest intervention studied, at 5 weeks, was $479 per student, whereas a 28-week program ranged from $6,696 to $10,108.

Besides the three levers (grade level, student scores, and program duration) that control costs, a major takeaway from the cost-effectiveness analysis study is the hefty price that is to be paid for each struggling reader.

At a time when students are recovering from missed learning opportunities due to the pandemic, it is not uncommon to see more than half of the class miss the mark for reading proficiency.

For example, in a class of 20 students, this means 10 students will require some level of reading intervention.

In kindergarten, considering the lower cost per student from the two sample cases in the study ($479), the costs amount to approximately $5,000 per classroom.

In grade 3, considering the lower cost per student from the two sample cases in the study ($6,696), the costs amount to approximately $65,000 per classroom.

Whichever way we look at it, reading intervention is a costly measure.

Reading Intervention Cost Comparison

Early Reading Intervention Program VS Sprig Reading

Footnotes

- Based on the following research studies:

https://amplify.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/mCLASS_MOY-Results_February-2022-Report.pdf

https://literacy.virginia.edu/sites/g/files/jsddwu1006/files/2022-04/PALS_StateReport_Fall_2021.pdf

https://www.chapinhall.org/wp-content/uploads/Reading_on_Grade_Level_111710.pdf

- # of students needing intervention = # of students x % not reaching reading proficiency

3. Note that these costs are averages and costs differ based on the reading intervention needs of each student. Based on the following research studies:

https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1020&context=cbcse

https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1089965.pdf

- Note that total costs assume there is a budget to support every student that requires reading intervention. In actuality, most school budgets will not cover every single student’s needs at each grade level. Total Costs = # of students requiring intervention x Average cost per student

5. Total Costs Per Grade = # of students requiring intervention x Average cost per student

As the table above shows, proven and successful early reading intervention programs can be very costly. For a typical school, costs can quickly add up to more than $275,000 for a year to support all students in need of early reading interventions. Now given this high price tag for a school (and school division), often difficult decisions are required to determine which students will receive the reading intervention support due to the lack of funds.

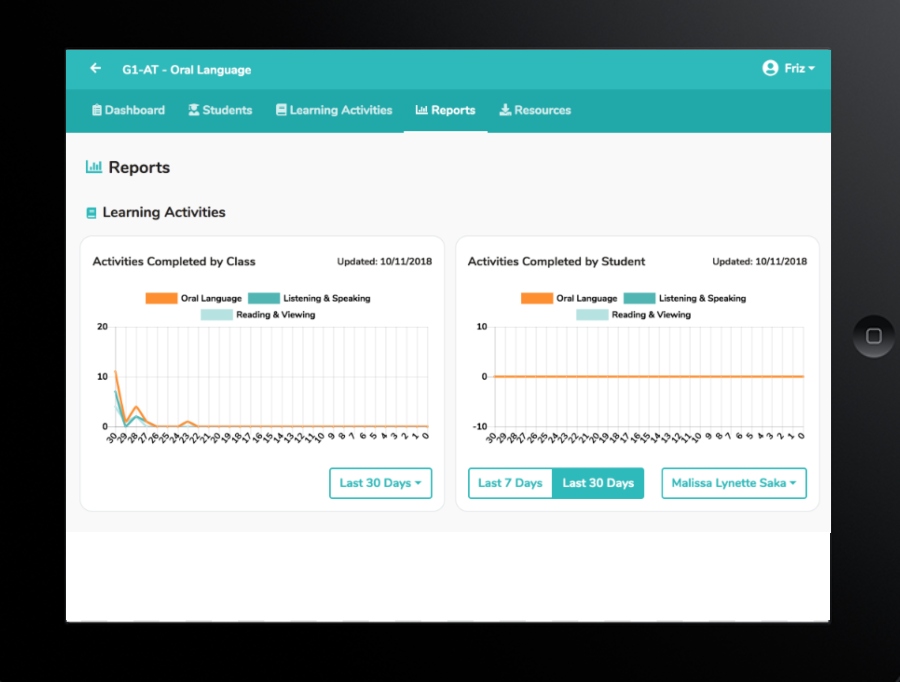

The table above further outlines the costs of Sprig Reading, an evidence-based early reading tool that supports teachers to assess, monitor, plan and instruct on the foundational reading skills. This program has repeatedly proven to bring over 90% of students to reading at grade-level.

In a typical school, the above table shows that when using an inclusive program like Sprig Reading, as early as pre-kindergarten and kindergarten, school costs can be drastically reduced as fewer students require more expensive reading intervention programs in grade 3 and beyond.

Sprig Reading is now available for purchase or a free trial on our website. Simply scroll down to the bottom of the page and choose the option that best suits you.

Reading Intervention Can Be Exclusive

Given the high costs of reading intervention programs, it cannot be guaranteed that every student who requires help will receive it.

Further, if students are not identified in kindergarten, latent gaps in foundational reading skills generally appear at the higher grade levels.

Not to mention, it is more costly to intervene at the higher grade levels, as seen in the last section.

Rather, if schools adopt a structured literacy inspired or evidence-based approach for the whole classroom, the likelihood of students requiring intervention decreases.

Maria Murray, president of The Reading League, a nonprofit, literacy organization out of New York, says that the gap in reading can be closed with “transformative change in the classroom—not just heaping on more programs”.

She goes on to say “Too often, it’s just an additive model with little to no attention to core classroom instruction and the knowledge that the teachers possess”.

Thus, in order to improve the methods of teaching reading to raise literacy scores, more attention needs to be paid in strengthening the curriculum and increasing the knowledge of educators.

In other words, early literacy efforts have to be widespread and inclusive. The preparation should be such that every student is ready to be helped with research-backed practices and teacher knowledge that minimizes the need for later intervention.

Addressing the Root of the Issue of Reading Interventions

There have been studies showing the efficiency of reading intervention programs in raising alphabetics and text reading fluency scores, albeit at a very high cost per unit increase in the effect size.

Two questions arise.

- Are intervention solutions reaching all students and are the gains being sustained? The reading achievement per grade level is still very low across North America. This suggests that there is room for improvement in both whole classroom coverage and skills retainment.

- Is this sustainable? Given how expensive reading intervention programs are per student, can they be sustained given the pressures from other academic needs such as after school tutoring, new teaching staff hires, and summer learning.

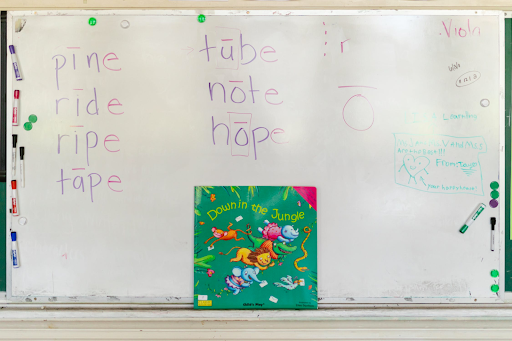

If the desired achievement results are not attained, it makes sense to try new evidence-based approaches that have the potential to reduce costs. For example, Stacy Pim, an elementary reading specialist in Virginia, noticed that the skills of Grade 1 students were not improving, and by Grade 2 most of them were reading below grade level. She took it upon herself to use more of her instruction time to teach students phonics-based components such as letter-sound correspondence. Only a year and half later, Virginia enacted a law mandating evidence-based literacy training and instruction.

EducationWeek reported that the most popular reading programs did in fact diverge from evidence-based practices in teaching struggling readers. Phonics is included as a component, but not in the systematic manner that is recommended by the Science of Reading. It is often challenging for teachers to organize classroom lessons in the correct sequence in such programs.

Reading Intervention Is Still Needed.

There will always be some students who require extra intensive support that can only be delivered using a pull-out method and with the help of early literacy specialists.

But Early and Only When Required.

Research says that 80% of students should be able to read in any environment or with explicit and direct high-quality tier 1 instruction, meant for the whole classroom.

An additional 15% of students can be moved to tier 1 with additional attention and support. This may mean actual reading intervention programs, or in-class differentiated small group instruction.

But it’s safe to say that no more than 20% of students should require reading intervention when early evidence-based approaches to early reading are implemented in kindergarten.

By focusing on early literacy tools that supplement or strengthen the foundational reading skills, it’s possible to greatly reduce the number of students requiring additional intervention programs later on.

This reduces expenditures for the school and school districts while simultaneously ensuring every student is on a track to achieve reading success grounded in strong foundational reading skills.

In the truest sense of the definition, it improves academic ROI!

Credits

<a href=”https://www.flaticon.com/free-icons/read” title=”read icons”>Read icons created by Freepik – Flaticon</a>