5 Hidden Gems for Teaching Reading in Schools

In early literacy, there is a growing body of evidence which outlines the best way to teach young children how to read.

Sprig Learning has covered these topics previously, such as highlighting the need for focused professional development, supporting existing roles such as principals, literacy coaches, and primary teachers, taking on projects aimed at alleviating literacy inequity, and dissecting evidence-based trends that are delivering results.

Furthermore, Sprig has covered the academic return on investment angle to achieving higher literacy scores, advised on the implementation of strategic reading instruction, and discussed the ideal cost-effective early reading intervention.

The linked articles above should provide plenty of reading material for anyone looking to understand the drivers of early literacy success and managing all aspects of policies, resources and systems that go into raising literacy scores for prekindergarten, kindergarten and elementary school children.

However, there is more information to process when it comes to teaching reading in schools and early learning centers.

More Gems for Teaching Reading and Developing Early Literacy

In Sprig’s research thus far, there have been advice and case studies that fell outside the purview of previously written articles. These bits of wisdom deserve to be highlighted however, as they have shown to be just as successful in closing the early literacy gap.

When these five gems of recommendations listed below were followed, schools and early learning centers were successfully able to surpass student language and literacy learning indicators targets.

1. Pinpoint Problem Areas in the Early Literacy Journey

Carmen Alvarez, Director of Early Childhood Learning in the Harlingen Consolidated Independent School District in Texas, vouches for the ability to see where a student needs help, rather than just understanding if they are progressing or not.

In her words “the ability for teachers to see the exact sounds a student is struggling with, and know which concepts students have mastered” are advantageous in teaching reading.

It’s one thing to pass students along based on if they have met certain reading qualification criteria. It’s another approach to specifically zero in on certain difficulties that could hamper reading proficiency in the future.

2. Integrated Reading Instruction for Holistic Reading Development

Dr. Gina Cervetti is an associate professor of Literacy, Language, and Culture at University of Michigan’s School of Education. She says that in the early years, “reading instruction needs to be integrated”.

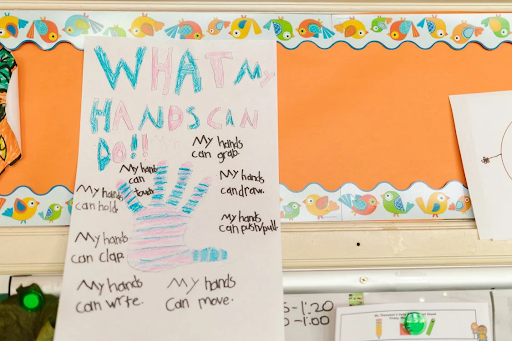

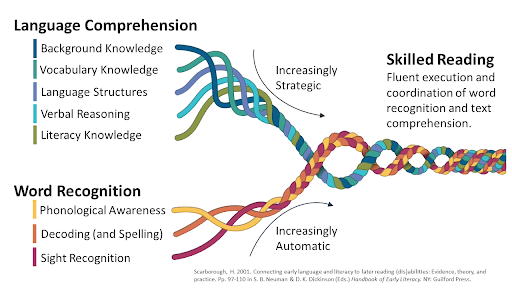

Learning the code of written language is critical, which deals with phonics and phonological awareness. Enriching conversations to develop student’s oral language and vocabulary is also critical in this equation for literacy success.

This is not to be confused with a balanced approach. According to the evidence, alphabet knowledge and phonics instruction should be direct and systematic and inclusive for the whole classroom. But alongside these practices, there should also be enough conversations and reading sessions to help practice the reading concepts that are being taught.

3. Specifically Devise Strategies for Those Student Groups Who Need Extra Support

Strategic reading instruction should involve regular assessments, systematic instruction, and appropriate interventions for the whole classroom, so the right support can be assigned to students who should be in a different tier of support all together.

Taking this bottom-up approach to instructional coverage ensures that every student receives an education that is of a high caliber, before being designated to another tier.

Being assigned to another tier without receiving an evidence-based high-quality education can sometimes be at the detriment of other students, who need those same resources more.

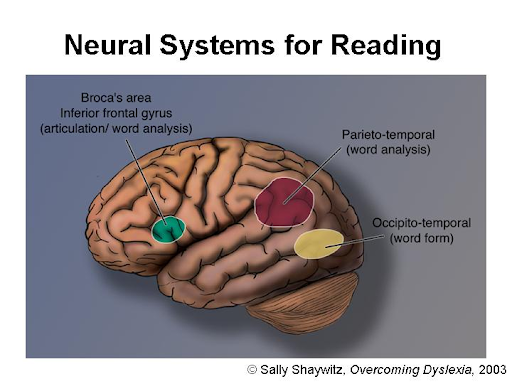

Sometimes however, a certain case may warrant devising a specific strategy for dealing with a certain group of students who are disadvantaged to begin with. This could be dyslexic students, or English Learner (EL) students.

Waltham Public Schools’s EL students grew to almost one fifth of the of the student body, which was twice the state average. These students fell behind their peers on foundational literacy measures and English and language arts assessments.

To address the issues Waltham established a new elementary school to establish a language immersion program, used funds to invest in a literacy professional development program for dual language program’s teachers, and created a summer program for the students.

4. Use a Co-Teaching Arrangement to Provide Greater Supports

Three districts in northern Berkshire County in Massachusetts, made the decision to collaborate in order to strengthen inclusive practices for kids in grades PK–2 through a special education audit and professional development.

A co-teaching approach was put into place where an occupational therapist was pushed into preschool and kindergarten classes to assist any students who needed it.

Push-in versus pull-out strategies for differentiated instruction have their own merits, but there is no doubt that push-in strategies are more inclusive.

Push-in strategies deem the early literacy recovery or acceleration efforts serious enough, where they want the presence of both the homeroom teacher and the other specialist professional inside the classroom. These types of strategies want every student to benefit from a situation where these professionals co-teach with homeroom teachers in the classroom.

5. Differentiate Instructional Strategy Based on Parent Participation

Active parental involvement is an indicator of early literacy success. Passive participation is when the school has to prompt the parent to contribute or engage in their child’s learning process. Active participation is when the parents collaborate with the teacher and the school by themselves, before being told to.

It’s great if parents have a way to see what is being taught, or receive insights into the learning strengths and weaknesses of their child, so they can offer help at home accordingly. But beyond active participation, what ends up happening at home is also important for teachers to know so they can take necessary measures.

For example, the Conejo Valley Neighborhood for Learning Early Childhood Program in Ventura County, California, said they would reinforce the importance of daily reading. But soon they discovered that some parents had limited access to books.

Upon learning this information, they “developed tips on how to use the same book repeatedly”. This specialized information was provided to those parents who needed this support.

The Best Way to Teach Reading in Schools

Along with the information covered in prior articles, Sprig hopes these 5 gems help schools and early learning centers to improve early literacy skills in students.

The best way to teach reading will ultimately depend on the situation at the said school, but seeing what has worked in other places is always good for drawing inspiration, tweaking current strategies, or implementing new ideas.

If you want more content on early literacy, be sure to check out the Sprig blog. We write blogs every week focusing on early reading instruction for both educators and administrators. Please consider joining our newsletter where you will be updated twice a month on the latest blogs, exclusive news from early learning and company updates.

A free trial of Sprig Reading is now available to all. It was developed accounting for many of the best practices teachers were using in the classroom to achieve up to 95% literacy at each grade level.

With Sprig Reading, instructors can quickly learn how to assess what children already know and what they still need to learn in order to help them develop into strong and independent readers.

Sprig Reading offers student-centered, classroom-tested instructional and assessment strategies to improve the reading ability of every child.

Both trial and subscription options are on the Sprig Reading page.